Monkey Business No More: Ninth Circuit Rules NFTs Are Protected by Trademark Law, Confirms the Limits of Expressive Speech Protection, but Overturns Judgment of Likely Confusion

By Sabrina Larson and Kat Gianelli

Key Takeaways

- The Ninth Circuit confirmed that non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are ‘goods’ under the Lanham Act and can be protected by trademark law.

- Even if a defendant uses a trademark owner’s mark with the goal of commentary and criticism, the fair use doctrine will not protect that use where the defendant uses the mark to designate its own goods.

- The First Amendment does not protect a defendant’s unlicensed use of a trademark when the use of the mark is at least partially acting as a source identifier, even if the defendant intended such use as satire and expressive speech.

- The decision is a win for brand owners promoting digital assets.

The Ninth Circuit ruled in Yuga Labs, Inc. v. Ryder Ripps on July 23, 2025 that non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are eligible for trademark protection under the Lanham Act, a significant development for creators of digital tokens. The Court also confirmed the limits of protection for satirical, expressive speech protection, where the defendant nonetheless uses the plaintiff’s trademarks as source identifiers.

The Court, however, overturned the lower court’s $8.8 million judgment for Yuga, finding that Yuga had not proven at summary judgment that the defendants’ tokens are likely to confuse NFT buyers.

Background

Yuga Labs, who created the NFT “Bored Ape Yacht Club,” sued artists Ryder Ripps and Jeremy Cahen for creating a nearly identical NFT titled “Ryder Ripps Bored Ape Yacht Club,” which was tied to the same ape images as Yuga’s NFTs. Yuga alleged trademark infringement and unlawful cybersquatting.

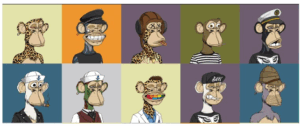

Examples of Yuga’s Bored Ape NFTs[1]

The defendants claimed their project was a satirical protest, and countersued alleging violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and sought declaratory relief that Yuga had no copyright protections over Bored Apes.

The district court granted summary judgment for Yuga on its trademark infringement claim and anti-cybersquatting claim, and also granted summary judgment for Yuga with regards to the defendants’ DMCA counterclaim, resulting in an $8.8 million judgment for Yuga, which the artists appealed.

Ninth Circuit Analysis and Decision

One of the defendants’ defenses was to argue that NFTs are not ‘goods’ under the Lanham Act, but the Ninth Circuit disagreed, holding that NFTs are protectable as ‘goods’ under the Lanham Act and affirming that Yuga’s “Bored Ape Yacht Club” trademarks are enforceable despite their digital nature. This conclusion aligns with the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office, which has also concluded that NFTs are ‘goods.’ The Court reasoned that NFTs are “more than a digital deed to or authentication of artwork” because they “also function as membership passes, providing ‘Ape holders’ with exclusive access to online and offline social clubs, branded merchandise, interactive digital spaces, and celebrity events.” The Court concluded, “Yuga’s NFTs are not merely monkey business and can be trademarked.”

The defendants also argued that they made nominative fair use of the Yuga marks. A common example of fair use is where one “‘deliberately uses another’s trademark or trade dress for the purposes of comparison, criticism, or point of reference.’”[2] The Court disagreed because the defendants used the Yuga marks not merely to reference Yuga’s NFTs, but as trademarks – that is, to create, promote, and sell their own NFTs. In that case, “[i]t does not matter that Defendants’ ultimate goal may have been criticism and commentary.”[3]

The Court also rejected the defendants’ argument under the First Amendment that their NFTs were part of an expressive art project and that the “expressive nature” of their use of the Yuga marks entitled them to an exception to trademark infringement for expressive speech. Again, the Court disagreed because this exception does not apply where the defendant uses the marks as source identifiers. “[W]hen a use of the plaintiff’s mark is ‘at least in part for source identification,’ the First Amendment exception to trademark enforcement is foreclosed.”[4]

Ultimately, the Court reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment on trademark infringement and cybersquatting claims against the defendants, finding that the likelihood of consumer confusion, which is central to both claims, presents factual disputes that must be resolved at trial. Although the defendants’ satirical use did not establish nominative fair use or protect the use of the marks under the First Amendment, the Court noted that that purpose created “significant questions about whether the likelihood-of-consumer-confusion requirement was satisfied.”

The panel affirmed the dismissal of the defendants’ counterclaims under the DMCA and for declaratory relief, concluding there was no evidence of knowing misrepresentation or an active copyright dispute.

Conclusion and Takeaways

The Ninth Circuit emphasized that “when we apply ‘established legal rules to the totally new problems’ of emerging technologies, our task is ‘not to embarrass the future.’”[5] This decision marks a significant step in adapting traditional intellectual property law to the evolving digital economy. It is a win for brand owners operating in the digital economy, opening the door for them to bring claims against infringing digital goods as they traditionally have against counterfeit products.

While the Court remanded for a determination of whether the defendants infringed Yuga’s marks, it clarified that NFTs are not exempt from the protections and tenets of trademark law in the Ninth Circuit – NFTs are ‘goods’ under trademark law, and trademark infringement analysis must be applied when those marks are used at least in part as source identifiers by the defendant even with the intention of criticism and satire.

[1] Yuga Labs Inc v. Ryder Ripps, 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, No. 24-879, Opinion (“Op.”) at 10.

[2] Op. at 34, quoting E.S.S. Ent. 2000, Inc. v. Rock Star Videos, Inc., 547 F.3d 1095, 1098 (9th Cir. 2008).

[3] Op. at 36. See Jack Daniel’s Props., Inc. v. VIP Prods. LLC, 599 U.S. 140, 148 (2023) (explaining a defendant does not get the benefit of fair use “even if engaging in parody, criticism, or commentary – when using the similar-looking mark ‘as a designation of source for the [defendant’s] own goods’” (alteration in original) (citation omitted)). See our analysis of the Jack Daniel’s decision here.

[4] Op. at 41, quoting Jack Daniel’s, 599 U.S at 156. See our analysis of the Jack Daniel’s decision here.

[5] Op. at 6, quoting TikTok Inc. v. Garland, 604 U.S. –, 145 S. Ct. 57, 62 (2025) (cleaned up and internal quotations omitted).